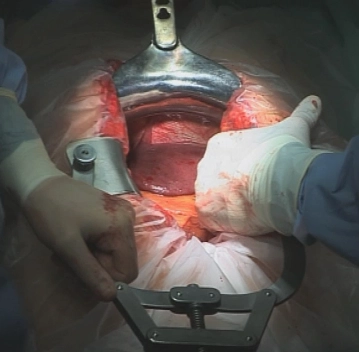

After sterile washing and covering as well as checking the positioning, a skin incision is made along the midline from the xiphoid to the umbilicus with left circumincision of the umbilicus. Opening of the abdominal cavity in the linea alba after transecting the subcutaneous tissue with the electrocautery.

Insertion of an inner covering foil and a Mercedes retractor as well as an Ulm retractor.

Exploration of the entire abdominal cavity to rule out peritoneal carcinomatosis and liver metastasis, if necessary by sonography.

-

Laparotomy and Exploration

![Laparotomy and Exploration]()

Soundsettings -

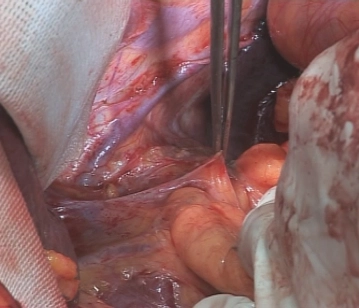

Mobilization of the intra-abdominal esophagus

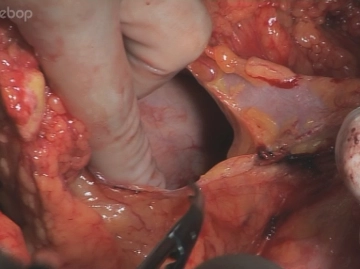

![Mobilization of the intra-abdominal esophagus]()

Soundsettings Incision near the liver of the lesser omentum. An atypical left hepatic artery originating from the left gastric artery, as present here, must be preserved. The incision is extended to the pre-esophageal peritoneum, the esophageal hiatus is bluntly opened in the cleavage plane between the right diaphragmatic crus and the esophagus. Blunt preparation of the esophagus cranially and to the left diaphragmatic crus. Slinging of the esophagus with a rubber band.

-

Opening of the esophageal hiatus with preparation of the distal esophagus

-

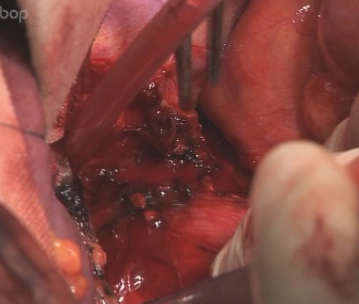

Duodenal Mobilization

![Duodenal Mobilization]()

Soundsettings To achieve a tension-free gastric interposition, an extensive Kocher duodenal mobilization is performed. This is done from the lateral side so far that the V. cava and the medial edge of the aorta are exposed. Subsequently, the duodenum and pancreatic head are so mobile that the pylorus can be guided upwards into the esophageal hiatus without difficulty.

-

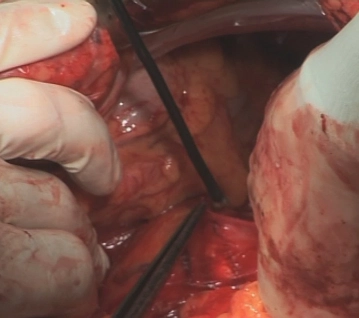

Opening of the omental bursa

![Opening of the omental bursa]()

Soundsettings Dissection of the greater omentum from the transverse colon and opening of the omental bursa. In this process, the greater omentum is initially left at the greater curvature. The greater omentum is detached close to the spleen in the area of the gastrosplenic ligament using Overholt clamps.

Tip: The spleen should be padded with an abdominal swab during the cranial dissection to prevent traction that can lead to tearing of the spleen; if necessary, a generous splenectomy must be performed.

Division of the short gastric vessels (Vasa brevia) while sparing the spleen. Releasing the gastric

Activate now and continue learning straight away.

Single Access

Activation of this course for 3 days.

Most popular offer

webop - Savings Flex

Combine our learning modules flexibly and save up to 50%.

US$87.98/ yearly payment

general and visceral surgery

Unlock all courses in this module.

US$176.00 / yearly payment

Webop is committed to education. That's why we offer all our content at a fair student rate.