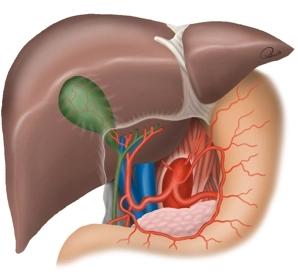

The bile duct transports bile from the liver to the duodenum. In this way, bile contributes to the digestion of fatty foods. The bile ducts begin intrahepatically with the right and left hepatic ducts (D. hepaticus dexter et sinister), which descend from the liver. At their confluence, these two ducts form the Ductus hepaticus communis. In the further course of this duct to the duodenum, the Ductus cysticus joins, which comes from the gallbladder (Vesica biliaris). Together, both form the Ductus choledochus, which opens into the duodenum. The Papilla duodeni major (Vater’s papilla) represents a sphincter that regulates the bile flow from the D. choledochus into the duodenum.

-

General Anatomy

![General Anatomy]()

-

Special Anatomy

The arterial supply of the gallbladder occurs in 75% via a single A. cystica, which branches off from the right A. hepatica running dorsal to the D. hepaticus dexter (see fig. above). In the remaining cases, the A. cystica branches off from other branches of the hepatic arteries or also from the A. gastroduodenalis and runs ventral to the D. hepaticus comm., or several arterial branches extend to the gallbladder. Therefore, if unclear bleeding occurs during the operation, it usually stops by compression of the A. hepatica in the Lig. hepatoduodenale or after placing a vascular clamp supraduodenally (so-called Pringle maneuver). Persistent bleeding may indicate an accessory hepatic artery from the A. mesenterica superior!

Anomalies of the D. cysticus are rarer than vascular variations, but of greater importance regarding the risk of injuries to the D. choledochus. The D. cysticus can empty into the biliary system at any point, including the papilla. Accordingly, the length of the D. cysticus varies; it can be very short or absent, run spirally in front of or behind the D. hepaticus comm., or share a common wall with it (duplication of the D. choledochus). In addition, accessory bile ducts from the liver can empty into the D. cysticus, the gallbladder, or the right D. hepaticus. If the D. cysticus is not clearly visible, there is the option to open the gallbladder and probe the duct from inside. Alternative: in unclear situations, intraoperative cholangiography!

Injuries to the D. choledochus result from anatomical anomalies or disease-related changes. Excessive traction on the D. cysticus can lead to placing the ligation clamp too deep, so that the edge of the choledochus is also captured and ligated! This then leads to transection or stenosis of the main bile duct.

-

Functional Liver Anatomy

![Functional Liver Anatomy]()

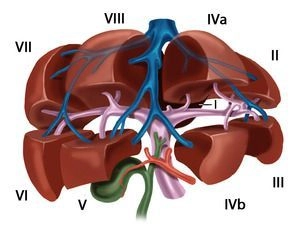

The liver is macroscopically divided into a larger right lobe and a smaller left lobe (volume ratio approx. 80 : 20) by the falciform ligament and the insertion of the ligamentum teres hepatis on the diaphragmatic surface, as well as the sagittal fissure on the visceral surface, although this morphological division does not correspond to the functional structure of the liver. The functional division of the liver is determined by the branching of the portal structures: portal vein, hepatic artery, and bile duct. These three anatomical structures branch not only at the porta hepatis, but also predominantly in the same direction within the parenchyma. Each liver segment is completely independent from the other segments in terms of blood supply and bile drainage and can be surgically removed without endangering the function of the remaining liver.

The term “functional anatomy” thus refers to a substructuring of the liver, which is based on the delimitability of hemodynamically independent parenchymal districts and whose knowledge is essential for the operative strategy in liver resection procedures.

-

Portal Vein and Hepatic Veins

The functional division of the liver is based on the portal branching into individual, independent subunits, the segments.

Usually, the portal vein divides in the hepatic hilum into a right and left main trunk. The boundary of these supply areas lies in the cava-gallbladder line (“Cantlie line”). Through renewed bifurcation of the respective portal vein trunk, an anteromedial and a posterolateral trunk arise on the right side for the liver segments V/VIII and VI/VII, respectively. The left main trunk extends transversely to the left and then as the pars umbilicaris anteriorly and ends at the insertion site of the ligamentum teres hepatis in the so-called recessus rex. The left portal main trunk gives off branches for the two left-lateral segments II and III as well as for the median segments IVa and IVb. The caudate lobe occupies a special position, as it can receive strong inflows from the left and also from the right portal vein main trunk.

According to Couinaud, eight portal venous liver segments are distinguished, which, starting with the caudate lobe as segment I, are numbered clockwise:

Segment I

Caudate lobe

Segment I/II/III

Lateral left hepatic lobe

Segment IV

Left paramedian sector (quadrate lobe)

Segment I/II/III/IV

Left half of the liver

Segment V/VIII

Right paramedian sector

Segment VI/VII

Right lateral sector

Segment V/VI/VII/VIII

Right half of the liver

The liver is traversed in a caudocranial direction by three main venous trunks, namely the right, middle, and left hepatic vein, which divide the liver into a total of four hepatic sectors. The left hepatic vein drains almost exclusively the left-lateral hepatic lobe and usually unites shortly before its entry into the vena cava with the middle hepatic vein, which runs along the cava-gallbladder line. The right hepatic vein runs between the posterolateral and anteromedial segments. The caudate lobe has its own venous drainage, which consists of multiple small veins emptying directly dorsally into the vena cava, the so-called Spieghel veins.

The portal hila of liver segments II, III, and IV lie extrahepatically and can be relatively easily dissected in the anterior section of the left umbilical fissure. The hila of the right-sided liver segments lie intrahepatically. Exceptions occur occasionally and usually concern segment VI. The anatomy of the hepatic veins is even more variable than that of the portal vein.

Variants

Portal Vein System

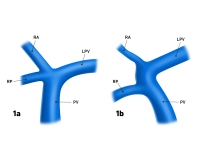

- Anomalies of the portal vein bifurcation almost always affect the right portal vein main trunk

- Portal vein trifurcation: right main trunk is absent, instead there are two branches for the right double segments V/VIII and VI/VII (Fig. 1a); occasionally, one of the right branches can also originate from the left portal vein main trunk (Fig.1b)

- Variants of the left portal vein system rarely affect the main trunk, but almost always the division: several small portal vein branches instead of two segmental branches IVa/IVb, occasionally also an additional, intermediate branch between the segmental branches II and III

Fig. 1a and 1b: PV = portal vein, LPV = left portal vein, RA = right anterior portal vein branch, RP = right posterior portal vein branch

Hepatic Veins

- Variants of the hepatic veins are more common than those of the portal vein system

- Deviations from the hepatic sectors described by Couinaud particularly affect the territories of the right and middle hepatic vein

The common hepatic artery originates from the celiac trunk; in rare cases, it has its origin direct

Activate now and continue learning straight away.

Single Access

Activation of this course for 3 days.

Most popular offer

webop - Savings Flex

Combine our learning modules flexibly and save up to 50%.

US$87.56/ yearly payment

general and visceral surgery

Unlock all courses in this module.

US$175.10 / yearly payment

Webop is committed to education. That's why we offer all our content at a fair student rate.