Pancreatic cancer is the fourth leading cause of cancer death in Europe and is expected to rank second in cancer mortality by 2030 [1]. The only potentially curative treatment option is surgical resection, which still achieves a 5-year survival rate of only 10% [2]. The aggressive tumor biology has led to the introduction of new, more effective chemotherapy regimens, both adjuvant and neoadjuvant, over the past 10 years, resulting in the establishment of multimodal therapy concepts.

Indication for Surgery

On the initiative of the German Society for General and Visceral Surgery (DGAV), evidence-based recommendations for the indication for surgery of pancreatic cancer have been defined, with the indication to be made by a tumor board of experienced pancreatic surgeons in accordance with guidelines, taking into account individual patient characteristics [3]. According to the recommendations, based on the systematic analysis of 58 original papers and 10 guidelines, there is an indication for surgery in histologically confirmed pancreatic cancer as well as in a high suspicion of a resectable pancreatic cancer [3, 4].

Resectability

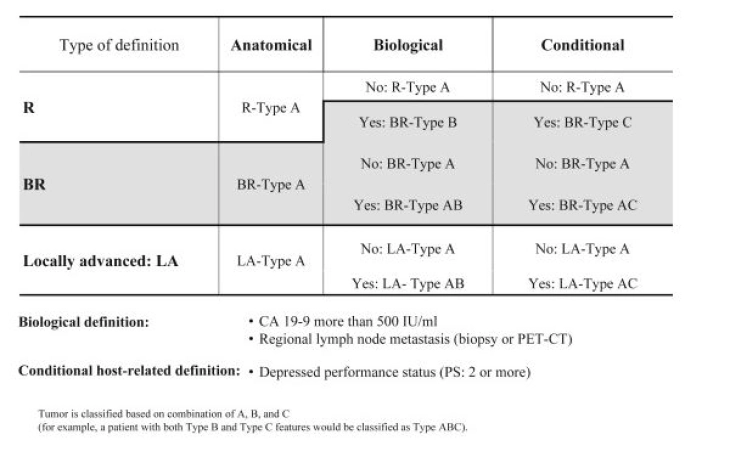

The greatest chance of survival is with resection in healthy tissue, the R0 resection [5, 6]. Current guidelines now divide the R0 classification into "R0 narrow" (≤ 1 mm) and "R0 wide" (> 1 mm), depending on whether the carcinoma reaches less or more than one millimeter to the resection margin [7]. In addition to anatomical resectability (relationship between tumor and major visceral vessels), tumor biology and the general condition of the patient have been considered as co-determining resectability criteria since 2017 and have been included in the current S3 guidelines as the ABC consensus classification of resectability [8].

ABC Criteria of Resectability According to the International Association of Pancreatology (IAP) Consensus

(Click to enlarge)

Source: Isaji S et al (2018) International consensus on definition and criteria of borderline resectable pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma 2017. Pancreatology18(1):2–11.

To assess anatomical resectability, the S3 guidelines recommend a contrast-enhanced 2-phase computed tomography [7]. Based on the anatomical resectability criteria, a tumor can be classified as primarily resectable, borderline resectable, and non-resectable or locally advanced [7].

The assessment of biological resectability is most often based on the tumor marker CA 19-9. The threshold was defined as > 500 IU/ml, as above this value, resectability is given in less than 70% of cases and survival of less than 20 months is expected [8, 9].

Another criterion is the ECOG Performance Status as conditional resectability, with patients having a status ≥ 2 having a poor prognosis [8].

Mesopancreas

The mesopancreas, the connective tissue region around the major vessels of the pancreatic region, which is densely traversed by blood and lymphatic vessels as well as nerve plexuses, has been discussed for several years [10]. Meta-analyses suggest that total mesopancreatic resection enables better oncological outcomes [11]. In pancreatic head resection, the complete removal of mesopancreatic tissue between the portal vein, hepatic artery, base of the celiac trunk, and superior mesenteric artery (Triangle Operation [12, 13]) is performed, while in left pancreatic resections (body, tail carcinomas), the radical antegrade modular pancreatosplenectomy (RAMPS [14]) is performed.

[RAMPS: Depending on the extent of the tumor, an anterior is distinguished from a posterior RAMPS procedure, in which essentially more radical resection is performed dorsally. In anterior RAMPS, resection is performed with removal of Gerota's fascia and perirenal fat on the left side. In contrast, in posterior RAMPS, in addition to Gerota's fascia and perirenal fat, the left adrenal gland is also resected.]

Vascular Resection

In centers, venous resections have minimally increased morbidity and mortality, and adequate overall survival is enabled [15, 16]. According to the current S3 guidelines, vascular resection of the portal vein can be performed in cases of tumor infiltration ≤ 180° or in complex situations such as cavernous transformation with reconstruction [17]. Arterial resections, on the other hand, are very risky, often complex, and frequently require simultaneous venous reconstructions. Patients often do not benefit oncologically from extensive procedures and often show worse survival data than patients without vascular resection [18]. Therefore, arterial resections should be avoided outside of centers.

Unexpected arterial resections can be avoided by early exposure to check for tumor-free status of the superior mesenteric artery and celiac trunk during a curative-intent pancreatic resection. The "Artery-first" strategy helps avoid futile procedures, allows better planning of vascular resections and reconstructions, and improves long-term survival for selected patients in centers with appropriate expertise [19].

Oligometastasis

The term oligometastasis appears for the first time in the current S3 guidelines and describes the presence of ≤ 3 metastases, which should only be resected within studies as part of a multimodal treatment concept [7]. No randomized studies are available yet, but resection of oligometastases seems to improve patient survival data compared to palliative chemotherapy, especially after neoadjuvant therapy [20 - 23]. In Germany, the HOLIPANC and METAPANC studies are currently addressing the issue [24].

Neoadjuvant Therapy Concepts

For patients with borderline resectable pancreatic cancer, the current guideline recommends preoperative chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy, while for resectable carcinomas, it should not be performed outside of studies [7]. The recommendations are based on data from a meta-analysis and currently published study data [25, 26]. Since after neoadjuvant therapy, resectability in initially borderline resectable and locally advanced pancreatic cancers is difficult to assess morphologically, the guideline recommends surgical exploration to assess secondary resectability in stable disease [7, 27]. A decrease in CA 19-9 levels can also help in assessing secondary resectability [28, 29].

Laparoscopic Techniques and Robotics in Pancreatic Cancer

Pancreatic left and pancreatic head resections must be considered separately. For left resections in laparoscopic technique, the randomized controlled LEOPARD study showed faster recovery, less blood loss, and no higher complication rate compared to the open technique [30]. The combined analysis of the LEOPARD and LAPOPS studies confirmed the data [31]. Long-term quality of life remains unchanged with the laparoscopic technique [32]. A meta-analysis of the existing data showed comparable results for the R0 resection rate and the rate of adjuvant chemotherapy [33]. The median overall survival was the same for laparoscopic and open pancreatic left resections at 28 and 31 months, respectively [34].

For pancreatic head resections, the 2019 published randomized and controlled LEOPARD-2 study showed higher mortality (90-day mortality 10%) in the laparoscopic group, which had no advantages over the open group in terms of postoperative pain, recovery, hospital stay, and quality of life [36]. A recent Chinese randomized study showed comparable mortality in laparoscopic pancreatic head resection with only slight advantage of the laparoscopic technique [37].

Robotics has also been established in pancreatic surgery over the past 10 years. In addition to the technically simpler left resection, pancreaticoduodenectomy is increasingly being performed. However, a long learning curve is required [37], and a final evaluation regarding oncological outcomes is not yet possible. Only observational studies are available on the use of robotics for malignant indications, demonstrating feasibility and potential advantages of the minimally invasive technique [38, 39, 40]. According to international guidelines, a malignant indication is not a fundamental contraindication for robotics, but results from randomized controlled trials and thus high-quality results are not expected for another 3 to 5 years [41].

Centralization of Pancreatic Surgery

In high-volume centers for pancreatic surgery, postoperative mortality can be reduced and survival increased [42, 43, 44]. Against this background, the minimum volumes for complex pancreatic procedures in Germany will be increased from the current 10 to 20 resections per year from 2024, as decided by the Joint Federal Committee.

Whipple Procedure versus Pylorus-Preserving Pancreatoduodenectomy (PPPD)

Two surgical procedures are considered for the resection of pancreatic head and periampullary carcinomas, the classic resection according to Kausch-Whipple and the pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy. The latter has the advantage of preserved physiological food passage and reduction of dumping syndromes, postoperative weight loss, and reflux [45-52].

More recent studies [49, 51, 52] have shown a lower transfusion rate and hospital stay for PPPD patients compared to the Whipple group. Postoperative morbidity did not differ significantly between the two groups. The occurrence of gastric emptying disorders was comparable in both groups (Whipple 23% vs. PPPD 22%). There was also no significant difference in surgical radicality (R0-Whipple 82.6% vs. R0-PPPD 73.6%). Long-term follow-up showed comparable overall survival rates.