Principles and Technique of Flexor Tendon Suture

Adhesions and scarring between the tendon and surrounding tissue, especially in the area of the flexor tendon sheaths, are the main problem in flexor tendon surgery. Adhesions can only be avoided by early movement of the tendon through passive, or better yet active, postoperative treatment concepts [1]. Since the suture site is mechanically loaded before the tendon has healed, high demands are placed on the stability of the suture.

If a rupture of the suture site occurs, this is due to mechanical overload of the suture material in 80% of cases. Knot formations can reduce the strength by up to 50% and lead to a significant weakening of the suture material [2]. In 20% of cases, the rupture of the suture site is due to the suture pulling out of the tendon tissue.

In the context of functional postoperative treatment, a creeping dehiscence can develop, i.e., a separation of the tendon stumps without rupture of the suture site. Dehiscences are caused by loosening of the suture in the tendon as well as intratendinous scar formation. Scars within the tendon represent a weak point that can lead to a later functionally disturbing elongation of the tendons. If the dehiscence is more than 3 mm, the strength of the suture no longer increases from the 10th postoperative day, which leads to a high risk of rupture [3].

Factors that can significantly impair the gliding ability of the suture include:

- bulging of the suture site due to overly tight pulling of the core suture

- introduction of excessive amounts of suture material

- suture material and knots not buried in the tendon tissue

- protruding fibers from the tendon stumps in the suture area

- dehiscences (see above)

The gliding ability of the tendon after reconstruction depends on the following parameters:

- technique of the core suture

- number of suture strands

- suture thickness, suture material

- technique of fine adaptation

For the technique of the core suture, it holds that thread guides in which the thread encircles the tendon fibers in such a way that tightening the suture results in closure of the loop (so-called locking suture) are significantly more stable than encircling sutures (10 – 50% [4, 5]). A classic example is the suture according to Kirchmayr-Kessler [6, 7]. The loop diameter should be larger than 2 mm, otherwise the loop can tear out [8]. Locking intermediate sutures can further increase the suture strength, but lead to uneven tension distribution in the suture, which can result in overloading of tendon strands [9].

The strength of a suture increases with the thickness of the suture material. Measurements on braided polyester threads show that the strength of a suture of thickness 4/0 is 64% higher than that of thickness 5/0. A thread of thickness 3/0 has a 43% higher tensile strength than a thread of thickness 4/0, a thread of thickness 2/0 compared to 3/0 by 63% [10]. Threads of thickness 5/0 are not suitable for core sutures due to their low strength [11].

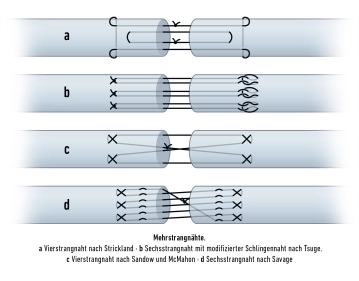

The strength of a flexor tendon suture increases with the number of loops and knot formations within the tendon [12]. These interactions between thread and tendon are referred to as anchor points. Suture techniques with a significantly higher number of anchor points compared to the simple Kirchmayr-Kessler suture increase the stability of the tendon reconstruction [13].

Various biomechanical studies have shown that the tensile strength of a flexor tendon suture increases proportionally to the number of suture strands, but decreases between the 5th and 21st day independently of the number of suture strands, although at different levels depending on the suture technique [2, 14]. For postoperative treatment after flexor tendon suture, this means:

- The tensile strength of a two-strand suture is sufficient for the loads of passive postoperative treatment, but not for active postoperative treatment without resistance.

- Only from a four-strand suture is there sufficient tensile strength for active postoperative treatment without resistance.

- No suture technique offers sufficient stability for maximum force application.

For the position of the knots, it holds that they should be buried in the tendon. Regarding tendon gliding ability, it should be most favorable if the knots are located in the suture site itself. However, this causes a certain dehiscence, and a knot also reduces the contact surface of the tendon stumps. If two knots are placed in the suture site, the contact surface is reduced by up to 27%, in the eight-strand suture according to Savage by up to 18%, in the Kirchmayr-Kessler suture by 2% [15, 16]. However, it is usually not a problem to bury the knot outside the suture site, as in the modification of the Kirchmayr-Kessler suture according to Zechner, which is demonstrated in the surgical procedure, step 6 in the clip [17].

The durability of the tendon suture also depends on the knot technique. A surgical knot that is tied 4 times is recommended [12]. A 4-time tied knot per suture results in higher tensile strength than multiple knots per suture, which is attributed to uneven distribution of suture tension and a decrease in tensile strength in the knot itself [2, 18, 19]. Placement of the sutures in the dorsal portions of the tendon is said to lead to higher stability [20, 21].

After tendon transection, degenerative changes occur in the adjacent sections of the tendon stumps, leading to a decrease in strength, which is why the anchor points should not be placed too close to the tendon stump. The most favorable position of the anchor points is at a distance of 7 to 10 mm from the tendon stump. A greater distance (> 12 mm) does not result in greater strength [22, 23].

After performing the core suture, a circumferential fine adaptation should be carried out to smooth the surface, increase tensile strength, and avoid dehiscences, in which the superficial tendon portions are inverted [24, 25, 26]. The fine adaptation must be performed with the finest suture material to not impair the gliding ability of the tendon by the externally located suture material.

There is currently no consensus on an optimal suture material for flexor tendon surgery. Among the currently frequently used non-resorbable suture materials are braided polyester threads, monofilament nylon, monofilament polypropylene, and threads made of braided polyethylene. For resorbable threads, sufficient durability of the material must be ensured, which is achieved, among others, by polydioxanone and polylactide [27, 28, 29].

Principles for Performing Flexor Tendon Sutures

rather favorable | rather unfavorable | |

Thread path in the tendon | locking sutures, locking intermediate knots | encircling sutures |

Thickness of the suture material | thread thickness 3/0 and 4/0 | thread thickness 5/0 and 2/0 |

Anchor points | large number, e.g., cross-stitch suture acc. to Becker | small number, e.g., Kirchmayr-Kessler suture |

Number of suture strands | ≥ 4 | 2 |

Knot position | in the tendon | outside the tendon |

Distance of anchor point from tendon stump | 7-10 mm | < 7 mm |

circumferential fine adaptation suture | yes | none |