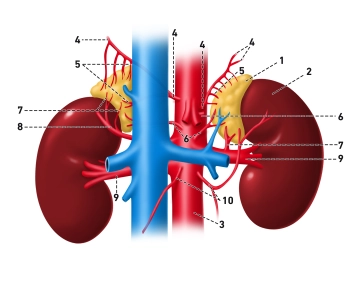

(1) Glandula suprarenalis, (2) Ren sinister, (3) Aorta abdominalis, (4) Aa. phrenicae inferiores, (5) Aa. suprarenales superiores, (6) Aa. suprarenales mediae, (7) Aa. suprarenales inferiores, (8) A. renalis accessoria aberrans, (9) Aa. renales, (10) Aa. testiculares

The adrenal glands (Glandulae suprarenales) lie as paired organs close to the upper pole of the kidney in the retroperitoneal space on both sides.

The right adrenal gland shows topographic relationships to the liver and the inferior vena cava, the left is separated from the posterior wall of the stomach by the omental bursa and extends to the spleen. Both adrenal glands are located approximately at the level of the 11th/12th thoracic vertebral body and are surrounded by a vascular connective tissue capsule that contains collagen fibers and smooth muscle cells. In adults, the weight of an adrenal gland is approximately 5-7 grams.

They are flattened in the dorsoventral direction, so that an anterior surface and posterior surface can be distinguished. The left adrenal gland has the shape of a crescent moon, the right one that of a triangular bishop's miter. The anterior surface of the left adrenal gland has a complete peritoneal covering, while the right adrenal gland is only covered by peritoneum in the caudal portion. The posterior surface of both adrenal glands lies on the lumbar part of the diaphragm.

The adrenal glands represent highly complex, dually controlled endocrine organs. Their asymmetric vascular anatomy, the close functional linkage of cortex and medulla, as well as their rich lymphatic and blood supply make them a central element of hormonal and autonomic balance in the human body.

The adrenal glands consist of two distinct parts – the cortex and the medulla. These areas differ both in their embryological origin and in their function. The adrenal cortex develops from the mesoderm and is histologically divided into three zones: the zona glomerulosa, the zona fasciculata, and the zona reticularis. Each of these layers produces specific hormones. The zona glomerulosa synthesizes mineralocorticoids, especially aldosterone, which regulates sodium and potassium balance as well as blood pressure. The zona fasciculata primarily forms glucocorticoids, mainly cortisol, which influence carbohydrate and protein metabolism as well as the stress response. The innermost layer, the zona reticularis, produces androgens to a lesser extent, which particularly contribute to the formation of male sex hormones in women.

The adrenal medulla arises from cells of the neural crest and is functionally assigned to the sympathetic nervous system. It consists of so-called chromaffin cells, which synthesize the catecholamines adrenaline and noradrenaline and release them in stress situations (“fight-or-flight” response).

The blood supply of the adrenal glands occurs via three arterial inflows: the A. suprarenalis superior (from the A. phrenica inferior), the A. suprarenalis media (directly from the abdominal aorta), and the A. suprarenalis inferior (from the A. renalis). There are numerous variants!

These arteries form a dense network under the capsule, from which capillaries branch into the cortical zones. The venous blood from the cortex then flows through the medulla before being drained via a central vein. This arrangement allows cortical hormones – especially cortisol – to reach the chromaffin cells of the medulla directly, where they can stimulate adrenaline production.

The venous drainage occurs via a single central vein each, the Vena suprarenalis. On the right side, the V. suprarenalis dextra is short and empties directly into the V. cava inferior. Due to its shortness and thin wall, it is considered particularly susceptible to injury, for example during surgical procedures on the right adrenal gland. On the left side, the blood flows via the V. suprarenalis sinistra, which usually empties into the V. renalis sinistra together with the V. phrenica inferior sinistra. The central veins of the adrenal glands have a characteristic spirally arranged smooth musculature that regulates blood flow and thus indirectly also hormone release.

The lymphatic drainage of the adrenal glands begins in a fine subcapsular capillary network that collects lymph from the cortex and medulla. The lymphatic vessels exiting the adrenal glands mostly follow the arteries. The primary lymph nodes are the Nodi lymphatici paraaortici et lumbales. Some lymphatic vessels pass through the diaphragm to the posterior mediastinal lymph nodes.

The innervation of the adrenal glands is mainly sympathetic. Preganglionic fibers from the thoracic spinal cord segments (Th5–L1) end directly at the chromaffin cells of the medulla, which thus functionally represent postganglionic neurons. Through this direct connection between the nervous system and the endocrine organ, catecholamine release can occur extremely quickly.

Functionally, the adrenal glands are central organs of hormonal regulation. The cortex is controlled via the hypothalamus-pituitary axis by adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), while the medulla is activated via the sympathetic nervous system. Together, they enable a coordinated adaptation of the organism to stress situations, regulate metabolic processes, water and electrolyte balance, as well as blood pressure.