Abdominal Wall Hernias

Primary (umbilical hernias, epigastric hernias) and secondary (incisional hernias) abdominal wall hernias are among the most common indications for surgery in general and visceral surgery. In 2018, 60,566 umbilical hernias, 49,387 incisional hernias, and 10,695 epigastric hernias were treated as inpatients in Germany [1]. Despite the frequency of these procedures, the evidence-based data for specific treatment decisions in the guidelines is considered insufficient [2, 3, 4, 5, 6].

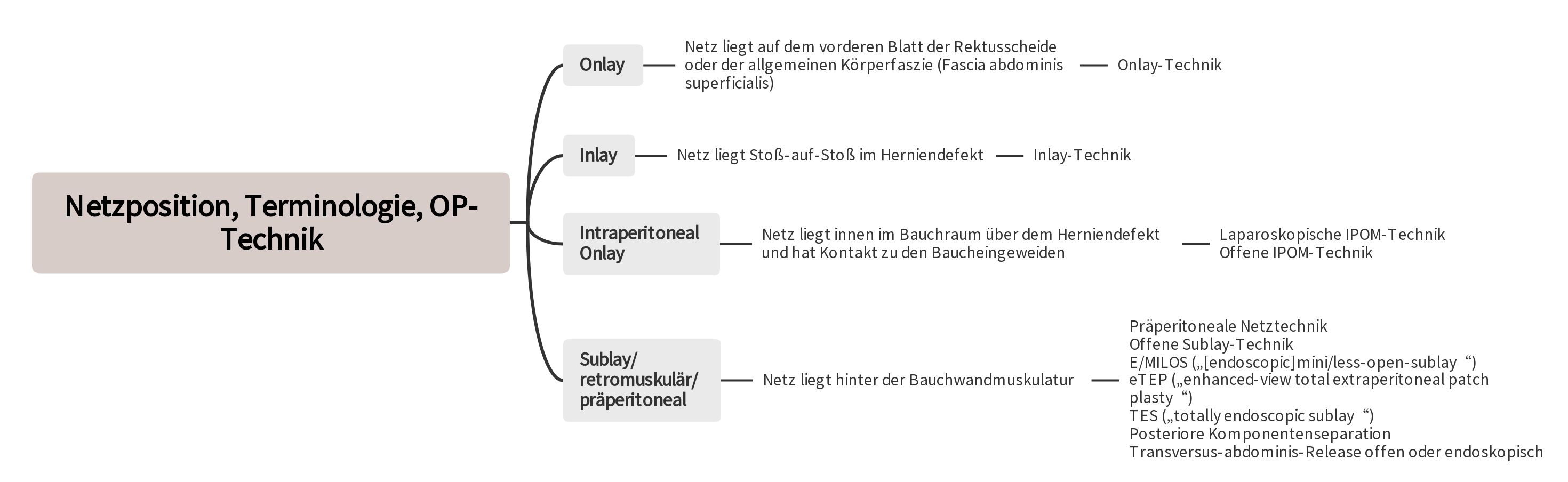

The use of mesh techniques represents the standard in the treatment of abdominal wall hernias [2, 3, 4, 5, 6]. In particular, the retromuscular positioning of the mesh behind the abdominal wall musculature and outside the abdominal cavity is considered preferred [2, 3, 4, 5, 6].

To reduce the high rate of wound complications in open operations and to avoid potential risks of mesh contact with the abdominal viscera in the IPOM technique, various innovative techniques have been developed [3, 4, 6]. These new approaches are characterized by the placement of the mesh through small incisions or endoscopically into the sublay/retromuscular/preperitoneal layer.

Classification of Abdominal Wall Hernias

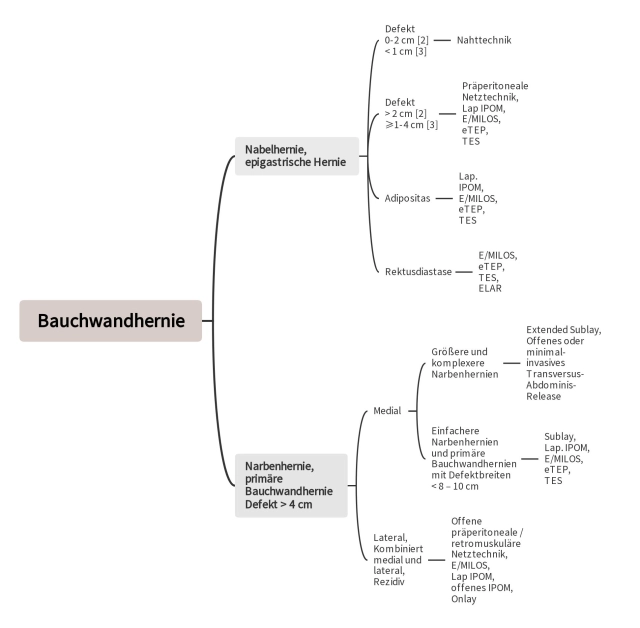

The European Hernia Society has developed a classification for primary and secondary abdominal wall hernias [7]. With regard to their defect diameter, primary abdominal wall hernias such as umbilical hernias and epigastric hernias are classified as small (< 2 cm), medium (≥ 2–4 cm), and large (> 4 cm). However, this simple classification for primary abdominal wall hernias in the midline is problematic, especially in the presence of concomitant rectus diastasis. In these situations, it is advisable to determine and consider the width and length of the rectus diastasis [8].

The classification of secondary abdominal wall hernias (incisional hernias) is initially based on the medial and lateral defect location in the abdominal wall. [7]). The defect location of medial incisional hernias is then more precisely defined with the specifications subxiphoid, epigastric, umbilical, infraumbilical, and suprapubic. For lateral defects, a distinction is made between subcostal, flank, iliac, and lumbar. Since the defect width has an unfavorable influence on the postoperative outcome in the treatment of incisional hernias, it is particularly considered in the classification. Depending on the defect width, incisional hernias vary in W1 (< 4 cm), W2 (≥ 4–10 cm), and W3 (> 10 cm) [7]. If multiple hernia defects exist (“Swiss-cheese” hernia), they are combined when measuring the length and width of the defect. Due to poorer outcomes, recurrent incisional hernias, which account for approximately 25% of the total incidence of incisional hernias, are classified separately [7, 9, 10].

Diagnostics

In the diagnosis of abdominal wall hernias, ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and computed tomography (CT) are used in addition to clinical examinations [11]. A systematic review on incisional hernia diagnostics concludes that the prevalence of incisional hernia increases when other diagnostic methods are applied compared to purely clinical examination [13]. When comparing the different diagnostic methods, the CT examination provides the most reliable results [11].

Abdominal wall hernias with defect widths of more than 10 cm are considered complex hernias [12]. A preoperative CT or MRI examination is increasingly required in these patients for planning the operative strategy and risk assessment, as component separation is usually necessary, about whose increased complication rate the patients must be informed preoperatively [13, 15]. A CT or MRI examination also provides information about the condition of the abdominal wall musculature, which is crucial for planning the appropriate reconstruction procedure [13].

Tailored Approach

For the treatment of abdominal wall hernias with a defect size of ≥ 2 cm, a mesh technique is recommended [2]. The guidelines of the European Hernia Society and the American Hernia Society indicate that the use of a mesh is indicated for epigastric and umbilical hernias with a diameter of ≥ 1 cm [3]. A suture procedure should only be used for defects of < 1 cm [3].

Due to the different recommendations, there is discretion for defects of 1 to 2 cm. For primary abdominal wall hernias, at least for a defect diameter of over 2 cm, a mesh procedure should be used [2, 3]. A preperitoneal mesh technique is recommended in the guidelines of the American Hernia Society and the European Hernia Society for defects up to 4 cm, although there is also the possibility to treat the defect using the minimally invasive sublay techniques E/MILOS, eTEP, or TES.

The aforementioned recommendations apply primarily to patients without obesity (body mass index [BMI] < 30 kg/m²) and/or rectus diastasis as well as defects up to 4 cm in diameter. Current studies show that in obesity, laparoscopic IPOM has a lower wound complication rate compared to open procedures for abdominal wall hernias [5, 6]. Therefore, minimally invasive techniques should be used primarily in obesity [5, 6]. New techniques such as E/MILOS, eTEP, and TES can be given priority to avoid the risks of intra-abdominal mesh placement, although there are no comparative studies yet.

In a primary abdominal wall hernia with concomitant rectus diastasis, preperitoneal mesh technique and laparoscopic IPOM are not sufficient [4, 5, 6]. Here, the new minimally invasive techniques offer themselves, in which the mesh is placed in the sublay layer [4, 5, 6]. Alternatively, the medial portions of the two anterior leaves of the rectus sheaths can be used to anatomically reconstruct the linea alba and close the defect. In the endoscopic-assisted linea alba reconstruction (ELAR), the mesh is used exclusively for augmentation [14].

For defects > 4 cm, proceed as with incisional hernias. After lateral, combined lateral and medial incisions, as well as after previous incisional hernia repairs with meshes, sublay techniques are usually not possible due to the significant scarring changes in the extraperitoneal/retromuscular layer.

Possible Risk Markers for Unfavorable Outcomes

An analysis shows that suture techniques for umbilical hernias with a diameter of less than 2 cm have a significantly higher recurrence rate compared to mesh techniques [15]. Female gender is also associated with a higher recurrence risk [15]. However, suture techniques have fewer postoperative complications. Although laparoscopic IPOM has a lower risk of postoperative complications for small (< 2 cm) umbilical hernias, intraoperative complications, recurrences, chronic pain, and general complications are more frequent [15].

For umbilical hernia with larger defect widths and open procedures, more postoperative complications, complication-related reoperations, and general complications must be expected [16]. The risk of rest- and load-dependent pain as well as chronic pain requiring therapy in the 1-year follow-up is increased in women and in pre-existing preoperative pain [16, 17]. An increased defect width, an elevated BMI, and a lateral defect location lead to significantly more recurrences [16].

Technical Aspects

1. Surgical Techniques for Primary Abdominal Wall Hernias

1.1 Suture Technique

For performing the suture technique in umbilical and epigastric hernias with defects of less than one centimeter, rapidly absorbable suture material is not recommended. However, there is only limited evidence in the literature for slowly absorbable and non-absorbable suture material [3]. Both a continuous and an interrupted suture technique can be used. The defect closure should be edge-to-edge.

1.2 Preperitoneal Mesh Technique

According to the guidelines of the European Hernia Society and the American Hernia Society, the preperitoneal mesh technique is recommended for umbilical and epigastric hernias with defects of ≥ 1–4 cm without rectus diastasis [3]. Defect enlargement to facilitate mesh placement should be avoided. To prevent direct contact of the abdominal viscera with the mesh, parts of the hernia sac are used to close the peritoneal gap. The non-absorbable mesh (usually round) should overlap the defect by 3 cm on all sides; accordingly, the peritoneum must be dissected from the abdominal wall on all sides around the defect. The fixation of the mesh is done with non-absorbable sutures. Afterward, the fascial defect is closed over the mesh with slowly or non-absorbable sutures.

2. Surgical Techniques for Primary and Secondary Abdominal Wall Hernias

2.1 Laparoscopic Intraperitoneal Onlay Mesh Technique

According to the guidelines of the European Hernia Society and the American Hernia Society, the laparoscopic IPOM technique is recommended for larger primary abdominal wall hernias and in patients with an increased risk of wound complications [3]. This particularly concerns patients with obesity (body mass index ≥ 30 kg/m²) and patients with a defect size of over 4 cm [3]. For incisional hernias, the defect should not exceed a size of 8-10 cm [5, 6]. When using the laparoscopic IPOM technique, defect closure should always be aimed for [3, 5, 6]. This reduces the seroma rate, avoids a remaining bulge of the abdominal wall, and minimizes recurrences [3, 5, 6]. The mesh must overlap the defect by at least 5 cm on all sides [3, 5, 6]. The fixation of the mesh is done with tackers and sutures [3, 5, 6].

2.2 Minimally Invasive Sublay Techniques E/MILOS, eTEP, and TES

The minimally invasive sublay techniques offer an alternative to the preperitoneal mesh technique and laparoscopic IPOM for primary abdominal wall hernias, especially in connection with obesity and/or rectus diastasis. For incisional hernias, they represent an alternative to open sublay surgery and laparoscopic IPOM when defects of 8-10 cm are present.

2.2.1 E/MILOS ([endoscopic]mini/less open sublay)

The E/MILOS operation is a minimally invasive hybrid procedure that enables the insertion of large synthetic meshes into the medial and lateral abdominal wall. The operation begins in a mini-open technique with incisions of up to 5 cm ("mini-open"), possibly 6-12 cm ("less open") [18, 19]. The dissection then proceeds transhernially either with light-armed laparoscopic instruments under direct vision or with gasless endoscopy. After the insertion of a single port or a gas-tight sealable optical trocar, the MILOS operation can be performed endoscopically [18, 19].

After classic dissection of the hernia sac and the fascial edges, the hernia sac is opened, the contents identified, repositioned, or resected. Intra-abdominal adhesions can be released either openly or laparoscopically through the hernia defect. After possible resection of excess hernia sac portions, the peritoneum is closed, and strictly extraperitoneal blunt dissection of the retromuscular layer follows. With complete dissection of the medial compartment, standard synthetic meshes up to a maximum size of approx. 40 × 20 cm can be placed flat on the mesh bed. Due to the defect overlap of the mesh of at least 5 cm, fixation can usually be dispensed with [4]. In the MILOS operation, posterior component separation is also possible. Giant hernias with “loss of domain” are not suitable for the MILOS technique.

2.2.2 eTEP (“extended totally extraperitoneal”)

The eTEP technique is based on experiences with totally extraperitoneal patch plasty (TEP) in the treatment of inguinal hernias [20]. For hernias at and above the umbilicus, the first access is chosen in the area of the right rectus sheath a few centimeters below the umbilicus [20]. After exposing the anterior leaf of the right rectus sheath, it is opened, the rectus muscle is lateralized, then a balloon trocar is introduced extraperitoneally and a corresponding space is dilated there. After inserting a gas-tight optical trocar and insufflation of CO2 gas, two working trocars can then be placed above the symphysis under vision. Subsequently, there is a change in working direction, in which both posterior leaves of the rectus sheaths are detached at the medial edge, thereby connecting both retrorectal spaces [20].

In the area of the umbilicus or proximal to it, one encounters the hernia sac. This is opened at the edge, the contents are repositioned or resected. Then, the two posterior leaves of the rectus sheaths are detached medially up to the xiphoid above the hernia gap. Through suture closure of the defect in the hernia area, the same retrorectal space is created as in the E/MILOS operation. A sufficiently large mesh can then be placed on the mesh bed consisting of the posterior leaves of the rectus sheath, the peritoneum, and the transversalis fascia [20]. Regarding the eTEP technique, there are various modifications concerning the accesses or positioning of the trocars [21].

2.2.3 TES (Totally Endoscopic Sublay Technique)

The TES technique differs from the eTEP method only in that the extraperitoneal space is not created through an optical trocar in the right rectus sheath below the umbilicus, but via an optical trocar directly above the symphysis and by creating the extraperitoneal space through blunt dissection. Once the extraperitoneal space is opened, two working trocars can be introduced under vision [22]. The further steps of dissection and mesh insertion then proceed according to the eTEP method [22].

3. ELAR (Endoscopic-Assisted Linea Alba Reconstruction)

Especially in young, slim women after childbirth, endoscopic-assisted linea alba reconstruction can be considered as a treatment alternative for primary abdominal wall hernias with concomitant rectus diastasis [4, 8, 14, 23].

In this method, an arcuate skin incision is made with left circumscription of the umbilicus, which is continued up to 2 cm proximally in the midline. Similar to the E/MILOS operation for repairing symptomatic umbilical and epigastric hernias, classic treatment of the hernia sac then follows. After dissecting the umbilicus from the abdominal wall fascia, the medial part of the two anterior leaves of the rectus sheath in the area of the rectus diastasis is dissected free. The dissection proceeds proximally and distally from the umbilicus until the distance between the two rectus muscles is only 2 cm, which, depending on the findings, may be necessary up to the xiphoid and far below the umbilicus. Dissection beyond the skin incision requires the use of a video-endoscopic camera with light source.

Subsequently, the anterior leaf of the rectus sheaths is incised about 1-2 cm from the medial edge, and the two medial portions of the anterior leaves of the rectus sheaths are adapted in the midline with a continuous, non-absorbable suture. This creates a new linea alba, the defects are closed, and the rectus musculature migrates back to the midline. For complete anatomical reconstruction, a mesh is sewn into the defect as a replacement for the anterior leaf of the rectus sheaths. This method is considered the simplest technique of component separation and is also performed without additional mesh reinforcement as "myofascial release" in plastic surgery [14, 23].

4. Surgical Techniques for Secondary Abdominal Wall Hernias

So far, laparoscopic IPOM and the sublay technique have been the usual surgical techniques for a simple incisional hernia with a defect width of < 8–10 cm [5,6]. Due to the possible dangers of intra-abdominal mesh placement, laparoscopic IPOM is increasingly being replaced by minimally invasive sublay techniques [24]. This led to the emergence of the “tailored retromuscular approach,” which means that the various retromuscular techniques (E/MILOS, eTEP and TES, sublay, posterior component separation/transversus abdominis release) are used depending on defect width and individual patient characteristics.

The basic techniques of E/MILOS, eTEP, TES, and laparoscopic IPOM have already been presented for primary abdominal wall hernias. That incisional hernias can be efficiently treated using the E/MILOS technique has already been demonstrated in comparison with open sublay surgery and laparoscopic IPOM [19].

4.1 Open Sublay Technique

The sublay technique describes a retromuscular preperitoneal position of the mesh, which ideally includes a midline reconstruction with closure of the fascia over the mesh. The mesh is implanted on the posterior leaf of the rectus sheath and the transversalis fascia under the rectus abdominis muscle [24]. A good mesh support with adequate blood supply and a lower infection risk are the reasons for the advantages of this technique. The intra-abdominal pressure in this surgical procedure rests on the mesh as the strongest component of the closure and supports its fixation. This allows a low recurrence rate to be achieved [25, 26].

4.2 Posterior Component Separation/Transversus Abdominis Release

The first steps of transversus abdominis release resemble the sublay technique. Therefore, the sublay operation can be extended intraoperatively to transversus abdominis release if, for larger defects, the detachment of the posterior leaves of the rectus sheaths is insufficient for defect closure due to lack of a sufficiently large mesh bed. The differential therapeutic considerations for midline incisional hernias with a defect width of ≥ 10 cm must take transversus abdominis release into account. A preoperative computed tomography is very useful for this.

With the detachment of the two posterior leaves of the rectus sheath from the xiphoid down to the arcuate line, the sublay part of the transversus abdominis release is completed. The space between xiphoid and “fatty triangle” is opened cranially, and the preperitoneal space between rectus muscles and transversalis fascia/peritoneum or symphysis and bladder is accessible caudally. This provides an extraperitoneal mesh bed on which meshes of 30 x 30 cm and larger can be placed.

According to initial publications, it is also possible to apply the open transversus abdominis release technique as a supplement to eTEP, E/MILOS, or robot-assisted [3, 27].

4.3 Open IPOM

An extraperitoneal or retromuscular mesh placement is usually not possible for incisional hernias after transverse, lateral, and combined medial-lateral incisions as well as for recurrences due to pronounced scarring [27]. In these cases, the open IPOM technique is the only treatment option [27]. Compared to the sublay technique, the open IPOM technique leads to more chronic pain in the 1-year follow-up [28]. In the literature, there is a considerable difference in postoperative complication and recurrence rates for open IPOM. A wide overlap of the mesh, avoidance of dissection in the abdominal wall, and defect closure are necessary to achieve better results with open IPOM [27]. It is also possible to use parts of the hernia sac for defect closure [27].

4.4 Open Onlay

A study found that the onlay technique has a comparatively high rate of postoperative complications compared to the sublay technique [29]. An examination of the Herniamed registry showed that there were no significant differences in outcomes for small and lateral incisional hernias between sublay and onlay techniques [30].

Adequate overlap of the mesh (at least 5 cm) and defect closure also lead to more favorable results in open onlay. It is also possible to use a doubled hernia sac for defect closure. Postoperatively, drainage and possibly abdominal binders should be used, as seromas occur more frequently in open onlay [29].

Robot-Assisted Surgery for Ventral Abdominal Wall Hernias

The development of robot-assisted retromuscular procedures has enabled significant advances in the surgery of ventral abdominal wall hernias. With the availability of robots, procedures with retromuscular mesh placement can now also be performed completely minimally invasively.

In 2018, Muysoms et al. and Belyansky et al. described robotic modifications of minimally invasive surgical procedures with retromuscular mesh reinforcement for completely minimally invasive treatment of abdominal wall hernias [31, 32]. While Muysoms described a robot-assisted transabdominal repair of umbilical hernias with retromuscular technique (robotic transabdominal retromuscular umbilical prosthetic hernia repair, r-TARUP), Belyansky favored an extraperitoneal access for a robotic "enhanced view totally extraperitoneal plasty" (r-eTEP). With the help of robotics, the transversus abdominis release established in open surgery is also possible minimally invasively [33].

So far, there are only completed randomized controlled trials with long-term follow-up on robotic IPOM mesh positioning. In a multicenter study by Dhanani et al., 124 patients were randomized, of whom 101 completed the 2-year follow-up [34]. While no significant differences in the perioperative course were found in the first publication, the analysis of the 2-year results now showed initial advantages of the robotic technique with a lower recurrence rate and a significantly lower reoperation rate [34, 35]. For retromuscular procedures, there are currently only systematic reviews and meta-analyses on the perioperative course; studies with longer follow-up are lacking.

In 2021, Bracale et al. published a meta-analysis that included studies published up to September 2020 comparing open and robotic transversus abdominis release [36]. In this systematic review, the robotic group showed a significantly lower overall complication rate, a significantly shorter hospital stay, and a significantly longer operating time. A statistically significant difference in the wound infection rate was not found.

In 2022, Dewulf et al. published a case-control study from two European hernia centers comparing the early postoperative outcomes of a total of 90 robotic and 79 open transversus abdominis release operations [37]. It was found that the duration of postoperative hospital stay was significantly shorter in the robotic group (3.4 vs. 6.9 days). In the open group, serious complications (20.3% vs. 7.8%) and wound complications occurred significantly more frequently (12.7% vs. 3.3%).