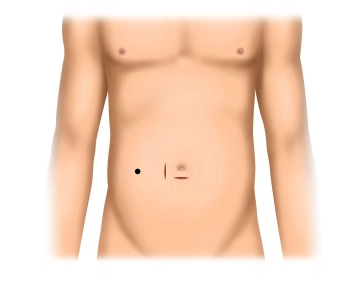

Infraumbilical skin incision, transection of the subcutaneous tissue and exposure of the fascia

-

Infraumbilical access

-

Exposure of the umbilical orifice

![Exposure of the umbilical orifice]()

Soundsettings The video clip can be played back with the automatic soundtrack of the subtitles.

In the sidebar registered users can enable and disable the automatic start of the dubbing.

Remark: Since this is a text-to-speech computer voice, it may mispronounce some medical terminology.Whenever present, use the umbilical orifice for trocar insertion (as demonstrated in this video clip). To do so, circumvent the umbilicus with a finger or blunt instrument and expose its insertion at the level of the fascia. Here, the umbilicus is sharply dissected off its insertion, thereby exposing the umbilical orifice. Now clamp the edges of the fascia with Mikulicz clamps.

Tip:

In planned peritoneal dialysis, the umbilical orifice must be carefully closed because otherwise the dialysate instilled into the abdominal cavity may result in herniation. If there is no umbilical orifice which may double as trocar access, the latter is established as usual in laparoscopy.

-

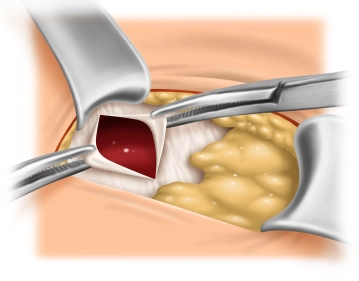

Initiation of pneumoperitoneum and inspection of the abdominal cavity

![Initiation of pneumoperitoneum and inspection of the abdominal cavity]()

Soundsettings The video clip can be played back with the automatic soundtrack of the subtitles.

In the sidebar registered users can enable and disable the automatic start of the dubbing.

Remark: Since this is a text-to-speech computer voice, it may mispronounce some medical terminology.Insert the trocar for the camera through a small incision of the peritoneum and establish the pressure controlled pneumoperitoneum. Insert the camera and inspect the abdominal cavity, paying particular attention to any adhesions which may affect the choice on which side the catheter will be inserted. While the video clip demonstrates adhesions after previous open appendectomy, these do not have to be taken down and the catheter may be inserted on the right side.

-

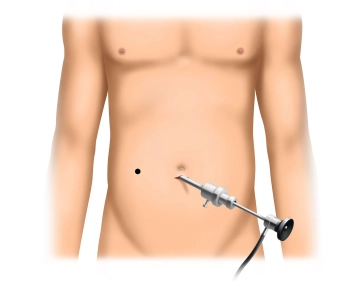

Threading the catheter

![Threading the catheter]()

Soundsettings The video clip can be played back with the automatic soundtrack of the subtitles.

In the sidebar registered users can enable and disable the automatic start of the dubbing.

Remark: Since this is a text-to-speech computer voice, it may mispronounce some medical terminology.Slip the catheter over the stylet. Accidental twisting of the catheter during this maneuver is best prevented by keeping the visible marker line on the catheter straight.

Tips:

- It is easier to slip the catheter over the stylet once it has been flushed with or soaked in saline.

- The catheter coiling should always point laterally (i.e., in the video clip with insertion in the right lower quadrant to the right). If after insertion the catheter coiling is located medially, the catheter tends to reposition the coil laterally which may result in catheter dislocation from the lesser pelvis.

Between the umbilicus and the planned catheter exit site incise the skin above the rectus muscle in

Activate now and continue learning straight away.

Single Access

Activation of this course for 3 days.

Most popular offer

webop - Savings Flex

Combine our learning modules flexibly and save up to 50%.

US$87.34/ yearly payment

general and visceral surgery

Unlock all courses in this module.

US$174.70 / yearly payment