The reconstructed abdominal wall with a mechanically stable laparotomy wound healed with satisfactory cosmesis is the visible expression of a successful operation.

Good fascial healing is achieved not by abundant but rather by little and adequately matured scar tissue. This meets the surgical requirements for a gentle technique as well as avoidance of wound infections, and high suture tension.

Incisional hernias are the most common long-term complication after laparotomy.

Optimized fascial healing is the key for preventing incisional hernias.

This requires the understanding that fascial suture only serves as a temporary support during local wound healing processes.

During the exudative phase (days 1-4) the wound has no tensile strength. The proliferative phase (days 5-20) sees the development of granulation tissue and the emergence of a new connective tissue matrix, which, however, only has 15-30% of the original tensile strength. Hematoma or wound infection may significantly prolong this process.

The required formation of scar tissue should not be considered as a static process, but rather as a chronic remodeling of the abdominal wall, even after years.

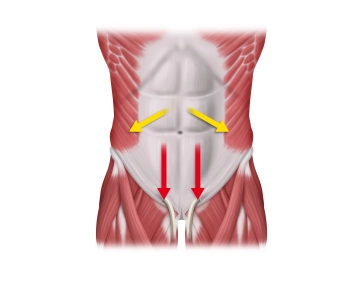

Continuous mass closure of the abdominal wall with a suture to wound length ratio of at least 4:1 with monofilament, delayed-absorbable sutures is superior to the interrupted suture technique. Its benefit is better biomechanical properties with favorable collagen synthesis along the incision as well as the economic aspect of significant savings in time and material. One important biomechanical factor appears to be the distribution of suture tension across small tissue bridges.

To prevent "buttonholes" from triggering incisional hernias, adequate tension of the running suture, adapting the edges of the fascia> with low strain on the tissue bridges, must be ensured during closure.

In addition, the elasticity of the suture material, corresponding to the physiological excursions of the abdominal wall, is another factor in preventing "buttonholing".