The stomach is, formally speaking, a dilation of the digestive tract located between the esophagus and the intestine, tasked with storing and mixing food. This muscular hollow organ produces acidic gastric juice (mucus and HCl) and enzymes that pre-digest some components of food, then gradually pass the chyme into the small intestine.

The stomach is usually located in the left and middle upper abdomen directly beneath the diaphragm. The position, size, and shape of the stomach vary greatly from person to person and depending on age, state of fullness, and body position. When moderately filled, the stomach is on average 25-30 cm long and has a storage capacity of 1.5 liters, and in extreme cases, up to 2.5 liters.

The stomach is anchored and stabilized in the abdominal cavity by ligaments that extend to the liver and spleen, among others. It forms the greater curvature (Curvatura major) with its convex side and the lesser curvature (Curvatura minor) with its concave side. Its anterior wall is referred to as Paries anterior, and its posterior wall as Paries posterior.

The stomach is intraperitoneal and thus covered by serosa, except for the dorsal cardia, which is free of serosa. The embryonic mesogastria rotate from their original sagittal position to a frontal one through gastric rotation: The lesser omentum extends from the lesser curvature to the liver hilum, while the greater omentum spreads from the greater curvature to the transverse colon, spleen, and diaphragm.

The stomach can be divided into different sections:

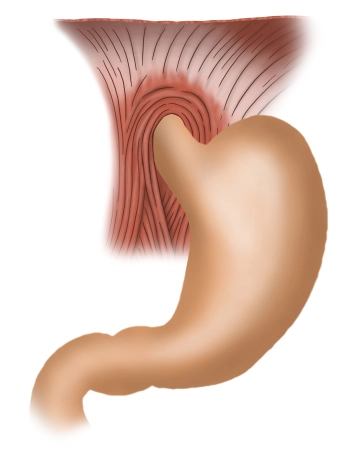

- Cardia / Ostium cardiacum:

The upper stomach entrance is an area of 1-2 cm where the esophagus opens into the stomach. Here, the sharp transition from esophageal mucosa to gastric mucosa is usually well visible with an endoscope. - Fundus gastricus:

Above the stomach entrance, the fundus arches upward, also called the "gastric dome" or Fornix gastricus. The fundus is typically filled with air that is involuntarily swallowed during eating. In an upright person, the fundus forms the highest point of the stomach, so in an X-ray, the collected air appears as a "gastric bubble." Opposite the stomach entrance, the fundus is demarcated by a sharp fold (Incisura cardialis). - Corpus gastricum:

The main part of the stomach is formed by the body of the stomach. Here, deep longitudinal mucosal folds (Plicae gastricae) extend from the stomach entrance to the pylorus and are also referred to as the "gastric street." - Pars pylorica:

This section begins with the expanded Antrum pyloricum, followed by the pyloric canal (Canalis pyloricus), and ends with the actual pylorus. Here lies the pyloric sphincter muscle (M. sphincter pylori), formed by a strong circular muscle layer, which closes the lower stomach opening (Ostium pyloricum). The pylorus closes the stomach exit and periodically allows some chyme to pass into the subsequent duodenum.