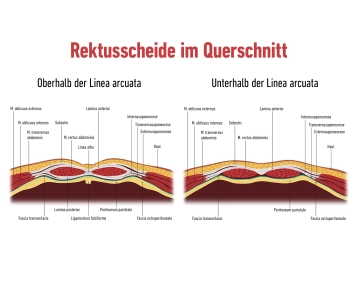

Rectus Sheath:

The rectus sheath is a firm, tendinous structure that envelops the anterior and posterior abdominal muscles. It is formed from the aponeuroses of the abdominal musculature:

External oblique muscle: The aponeurosis of this muscle forms a significant part of the anterior rectus sheath.

Internal oblique muscle: This aponeurosis splits above the arcuate line into an anterior and posterior portion, forming both the anterior and posterior layers of the rectus sheath.

Transversus abdominis muscle: Its aponeurosis reinforces the posterior layer of the rectus sheath above the arcuate line. Below this line, all aponeuroses contribute to the anterior layer.

The rectus sheath is connected at the linea alba, a vertical tendinous structure extending from the xiphoid process of the sternum to the pubic symphysis.

Important anatomical structures run within the rectus sheath, such as the superior epigastric artery and vein (above the arcuate line) and the inferior epigastric artery and vein (below the arcuate line). These blood vessels supply the abdominal wall and must be preserved during surgical procedures.

The rectus sheath provides stability and protection for the underlying rectus abdominis muscle as well as the intra-abdominal contents and is essential for the integrity of the abdominal wall.

Along the linea alba, a tendinous connection between the rectus sheaths, a surgical approach can be created. This region is relatively avascular, minimizing bleeding.