Esophagus

General Characteristics

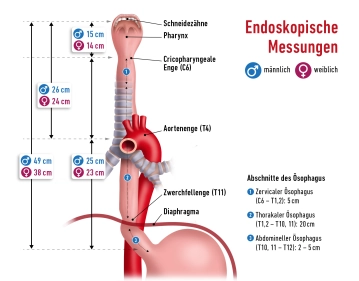

- Muscular hollow organ, approx. 25–30 cm long

- Connects pharynx (C6) with the stomach (Th11)

- Three constrictions:

- Upper constriction – cricoid constriction (transition pharynx/esophagus, at level C6)

- Middle constriction – aortic constriction (crossing with aortic arch + left main bronchus)

- Lower constriction – diaphragmatic constriction (esophageal hiatus, Th10)

Topographical Sections

Cervical Esophagus (C6–Th1)

- Behind the trachea

- Accompanying structure: recurrent laryngeal nerve

- Access: transcervical, ventral-lateral

Thoracic Esophagus (Th1–Th10)

- Upper mediastinum: behind trachea, in front of spine

- Middle mediastinum: behind heart and pericardium

- Crossing by aortic arch, azygos vein, left main bronchus

- Access: right-thoracic (better overview)

Abdominal Esophagus (short, 1-3 cm)

- Passes through esophageal hiatus (Th10) into the abdomen

- Empties into the cardia region of the stomach

- Accompanying structures: anterior vagal trunk (left), posterior (right)

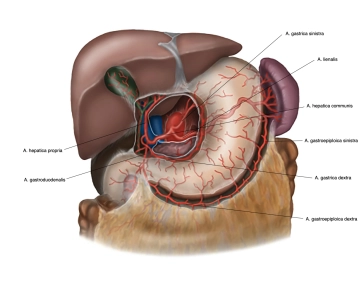

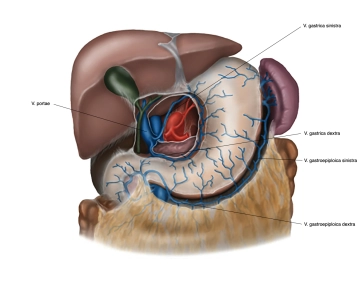

Stomach

General & Location

- Muscular hollow organ between esophagus and duodenum

- Located in the left/middle upper abdomen, directly under the diaphragm

- Can vary greatly in size and shape depending on age, filling state, and body position

- Great interindividual differences in terms of location, size, and shape

Size & Filling Capacity

- Average length: 25–30 cm (with moderate filling)

- Storage capacity: approx. 1.5 liters, in extreme cases up to 2.5 liters

Stomach Layers and Attachment

- Located intraperitoneally; mostly covered with serosa (except dorsal cardia)

- Embryonic mesogastria rotate into a frontal position:

- Lesser omentum: from the lesser curvature to the hepatic portal

- Greater omentum: from the greater curvature to the transverse colon, spleen, and diaphragm

- Attachment and stabilization by ligaments that, among other things, extend to the liver and spleen

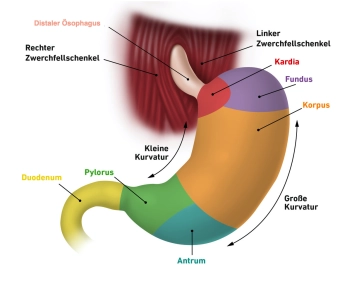

Sections of the Stomach

- Cardia (stomach entrance, upper gastric orifice, ostium cardiacum)

- Area of 1–2 cm in which the esophagus empties into the stomach

- Distinct transition from esophageal mucosa to gastric mucosa (clearly visible on endoscopy)

- Gastric Fundus (stomach fundus)

- Located above the stomach entrance, bulges upward

- Also referred to as gastric dome or fornix gastricus

- Typically filled with air; in upright position the highest point, recognizable as “gastric bubble” on X-ray

- Delimited from the stomach entrance by the cardiac notch

- Gastric Corpus (stomach body)

- Main part of the stomach

- Characterized by deep longitudinal mucosal folds (plicae gastricae) that run from the stomach entrance to the pylorus (“gastric canal”)

- Pylorus (pyloric part, pyloric sphincter)

- Beginning with the expanded pyloric antrum, followed by pyloric canal (canalis pyloricus)

- Ends with the actual pyloric sphincter (pylorus), where the pyloric sphincter muscle (M. sphincter pylori) is located

- Closes the stomach outlet (ostium pyloricum) and regulates the passage of chyme into the duodenum

Formal Boundaries and Further Anatomical Features

- Greater curvature (convex side)

- Lesser curvature (concave side)

- Anterior wall: Paries anterior; Posterior wall: Paries posterior

- Greater omentum originates from the greater curvature; Lesser omentum spans between the left hepatic lobe and the lesser curvature